Concarneau is a beautiful place to be stuck for a week without crew. The mediaeval walled town, on an island in the entrance to the river Moros, teems with tourists during the day but empties in the evening and you can stroll round the ramparts in the cool to look down on your boat in the town marina.

The quays upriver from the walled town form one of the biggest fishing ports in France so the seafood in the market and the restaurants around the harbour is spectacular. The shellfish stall inside the entrance of the market offers half a dozen different types and qualities of oyster, not to mention a bottle of chilled Muscadet for €5.

Awkward-sized, poorly manoeuvrable visitors berth on the breakwater pontoon on the outside of the marina under the walls of the Ville Close. My friends Andy and Amina stopped off in their bilge-keeler for coffee at the start of a long haul from the muddy creek where they keep her to Roscoff on the north Brittany coast and Plymouth.

When Chris, John and Lewis arrived a couple of days later, we headed south-east with all sails up and anchored at Port Manec’h, the entrance to the rivers Aven and Bélon, where Lewis jumped straight in before rowing Chris ashore for a beer.

Cloudless, hot weather can’t last and thunderstorms were forecast for the evening when we set sail next day for the Îles de Glénan, an archipelago of small, sandy islands which my friend Eric, who’s 93 and spent years sailing the Brittany coast, had been urging me to visit.

Because of the forecast, we stayed only long enough for a swim ashore and lunch on the boat but he’s right, the islands are magical. The sand is white, the sea is blue and with no other land in sight you feel as if you’re in the middle of the ocean although you’re only five miles offshore.

We anchored off the Île de Penfret, which is a sailing holiday camp for teenagers. Looking across the water less than a mile to the gentle hump of the Île de Guirden, dozens of holidaymakers with beach umbrellas were silhouetted against the horizon and looked like shipwreck survivors on a desert island.

We sailed north and sheltered from the thunderstorms in the marina at Benodet, where a fierce tide flooding up the river Odet ran across the visitors’ pontoon and made berthing an adventure. Leaving the next morning was even more difficult but fast work by John, Lewis and Chris kept fenders between the boat and the corner of the pontoon.

Excitement over, we motored quietly upriver between steep, wooded banks. I saw a kingfisher for the first time in my life, a flash of blue. Chris, who saw one first, spotted three. John is a bird encyclopedia and taught us much throughout the trip, including how to identify types of egret by the colour of their feet and how to recognise the call of a tawny owl.

All the anchorages on the chart were full of boats on buoys except for one creek near the entrance to the river where we saw a catamaran under the trees. We nosed in soon after low tide but the bow stuck in mud and it took heroic rowing by Lewis in the dinghy and a rising tide to free us. We retreated downriver to the marina at Sainte-Marine, opposite Benodet, which seemed as peaceful and relaxed as Benodet had been brusque and touristy. The stream even ran straight up and down the pontoon so berthing was much easier.

Two days of fine sailing brought us west and north to Camaret-sur-Mer on the south side of the approach to Brest in time for a birthday dinner for Lewis.

Camaret is famous for its seventeenth-century ‘Vauban Tower’, built by Cardinal Richelieu’s leading military architect Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban as a central link in a chain of fortifications guarding France’s naval base in Brest. It has a gun battery at its base and provided an observation platform covering the whole of Camaret Bay, which was the anchorage where ships waited for favourable wind and tide to pass through the Goulet de Brest to the port.

Before the Tower was even finished, it helped to defeat an Anglo-Dutch fleet which tried to capture Camaret in the Nine Years War, when William III led a Protestant coalition against Catholic France.

From Camaret, we beat through the Goulet de Brest with the tide under us and reached gently across the Rade de Brest to the river Aulne, which is where the French navy mothballs unwanted warships. We anchored on a peaceful stretch of the river within sight of what looked like the bar at the end of the world, an isolated wooden cabin just above the high water line. Lewis rowed ashore but sadly it was closed.

In Brest, we headed straight for the Crabe Marteau, the ‘Crab and Hammer’ restaurant where dinner consists of a crab served with a wooden mallet and a bucket of potatoes.

In Brest, I was acutely conscious, as the last time I was here, of the second world war. The modern city is built on the rubble of the old one which was bombed and shelled incessantly by the Allies when it was occupied by the Nazi Germans.

John, Chris and I visited the moving Sadi Carnot Shelter, a 400-metre tunnel from the port to the centre of the city in which civilians sheltered from Allied bombing but German soldiers also stored ammunition. On the night of September 9th, 1943, an accidental explosion and fire killed at least 375 civilians and several hundred German soldiers.

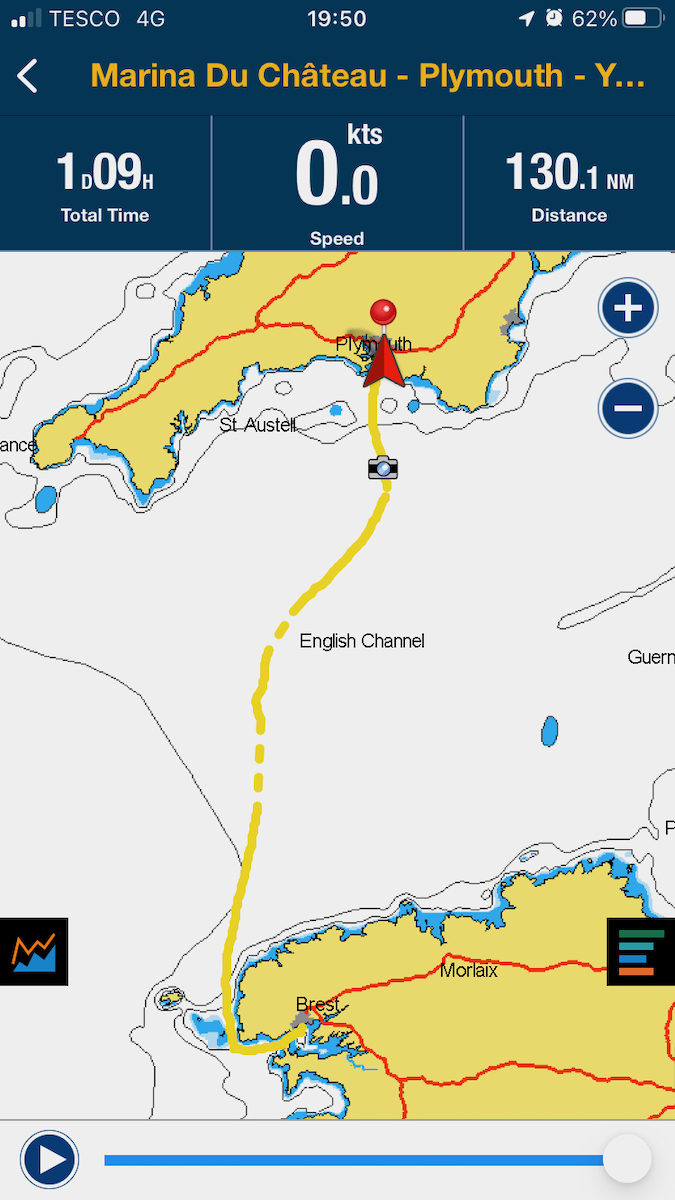

From Brest, we set out for Plymouth on a wet and misty morning and had the excitement of being ordered out of the way by Traffic Control to let a French nuclear submarine escorted by three gunboats pass through the Goulet de Brest.

A forecast Force 6 had already passed up the Channel but Chris and Lewis did endure one watch of torrential rain in the afternoon before the sun set in a mass of pink clouds. The southwesterly was blowing from too directly behind us to head directly for Plymouth for the first twelve hours but luckily it veered overnight and we made landfall on a warm, sunny day without having to tack, the perfect end to a summer in France.